To prevent your e-bike from becoming a worthless “brick,” you must evaluate its entire repair ecosystem, not just its features at the point of sale.

- Proprietary “digital handshakes” can block the use of third-party batteries and components, creating a dependency on a single manufacturer.

- Open-source motor systems (like Bafang) often allow for component-level repairs, whereas closed systems (like Shimano) typically require costly full-unit replacements.

- A comprehensive local warranty is a critical financial safety net against high, often un-budgeted, labor costs for specialized repairs.

Recommendation: Before buying, conduct a “serviceability audit” by asking the dealer pointed questions about parts availability, replacement costs, and third-party compatibility to secure your long-term investment.

The fear is palpable for any thoughtful e-bike buyer: you spend thousands on a state-of-the-art machine, only for it to become an expensive, unfixable paperweight a few years down the line. This concern isn’t just about a part failing; it’s about discovering that the replacement part is either astronomically expensive, no longer exists, or that the bike’s software actively rejects any non-original component. This is the central battleground of the e-bike “Right to Repair” movement.

Most advice simply tells you to “buy from a good brand” or “check the warranty.” While not wrong, this guidance is dangerously superficial. It overlooks the systemic design choices that determine whether your bike is a durable, long-term vehicle or a disposable electronic good. The true measure of an e-bike’s longevity isn’t its initial build quality, but the robustness and openness of its entire repair ecosystem. The manufacturer’s philosophy on parts, software, and independent servicing is the most critical factor for your long-term ownership experience.

But what if the key to a lasting investment wasn’t just in the hardware, but in understanding the “digital handshake” between components? The real risk isn’t just a part failing, but the system being deliberately engineered to prevent you from fixing it. This guide will provide you with the strategic framework to de-risk your purchase. We will dissect the mechanisms of proprietary lock-in, compare open and closed systems, and give you the tools to conduct a “serviceability audit” before you buy, ensuring your investment remains on the road for years, not just for the length of its warranty.

This article will guide you through the critical factors that determine the long-term repairability of your e-bike. By understanding these points, you can make a more informed and secure investment.

Summary: Proprietary vs Standard Parts: The Right to Repair Your E-Bike

- Why Integrated Batteries Are Harder to Replace Than External Ones

- How to Find Spares for Discontinued Motor Systems

- Shimano vs Bafang: Which Has Better Global Parts Availability?

- The Risk of DRMs Preventing Third-Party Battery Use

- Consumables to Stock: What to Buy Before It Goes Out of Stock

- Why a 2-Year Local Warranty Is Worth $500 More

- Why Chains Wear Out Faster on E-Bikes (And How to Check)

- The Hidden Value of Buying from a Certified Bosch/Shimano Service Center

Why Integrated Batteries Are Harder to Replace Than External Ones

The sleek, clean look of an integrated battery is a major selling point, but it often conceals a significant repairability challenge. Unlike external batteries that can often be swapped between models with similar mounts, integrated batteries are custom-shaped to fit a specific frame. When that model is discontinued, the supply of bespoke replacement batteries dries up, leaving owners with few options. This creates a high risk of your bike becoming unusable due to a single, unavailable component.

The problem goes beyond physical shape. High-end systems increasingly use advanced communication protocols to link the battery, motor, and display. This “digital handshake” ensures all parts are from the same manufacturer. According to a communication protocol analysis, systems like CAN bus are prevalent in performance e-bikes, creating a closed ecosystem. If the battery’s internal Battery Management System (BMS) fails or cannot communicate correctly with the motor, the entire system may refuse to power on, even if the battery cells themselves are healthy. This effectively prevents the use of third-party or refurbished batteries.

Therefore, a prospective buyer must shift their mindset from a consumer to an auditor. You aren’t just buying a bike; you are investing in a parts supply chain. Before committing, it’s crucial to perform a serviceability audit focused on this single, vital component. This proactive step is your best defense against future obsolescence.

Your Pre-Purchase Battery Serviceability Audit

- Verify Protocol: Ask the dealer to confirm the battery’s communication protocol (e.g., CAN bus, UART). A CAN bus system is a red flag for proprietary lock-in.

- Request Guarantees: Ask for the manufacturer’s guaranteed parts availability period in writing. How long will they produce this specific battery after the bike model is discontinued?

- Confirm Replacement Cost: Get a written quote for the current out-of-warranty replacement cost. This number is a crucial part of your total cost of ownership calculation.

- Check for Digital Handshakes: Inquire if the battery’s BMS has proprietary “handshake” requirements that would prevent a third-party battery from functioning.

- Investigate Re-celling Services: Research if third-party services in your area can replace the cells inside your specific battery casing. This can be a last-resort lifeline.

How to Find Spares for Discontinued Motor Systems

When a motor system is discontinued, owners often find themselves on a frustrating scavenger hunt for parts. Unlike the standardized world of non-electric bike components, e-bike motors are frequently sold as sealed, non-serviceable units. Manufacturers often restrict the sale of individual internal parts like gears, sensors, or controller boards, pushing for a full motor replacement that can cost a substantial fraction of the bike’s original price.

This forces owners and independent shops into the secondary market, searching for “donor” bikes or trawling online marketplaces for used or salvaged components. This is an unreliable and time-consuming process with no guarantee of success or part quality. The lack of industry standardization means that even within the same brand, parts from different model years are rarely compatible.

Case Study: The Independent Repair Shop’s Dilemma

GoodTurn Cycles, a shop in the Denver area, exemplifies the struggle. They are one of the few shops willing to attempt e-bike repairs precisely because of these issues. They frequently resort to third-party websites like Amazon, hunting for compatible components. The shop notes that due to a lack of standardization, “you could have four bikes and they would have very, very few parts that would actually be compatible with each other.” This highlights how a restricted repair ecosystem directly impacts even professional mechanics, making repairs a gamble rather than a standard procedure.

The most viable, though often costly, strategy for long-term ownership of a bike with a discontinued motor is to source a complete, functional used motor as a spare. This provides a backup for when the original unit fails, but it’s a significant upfront investment in “parts sovereignty.”

This reality of scavenging for parts underscores the importance of choosing a system with a long market presence and a known track record for parts availability. A niche, unproven motor system might offer great performance today but become a dead end tomorrow.

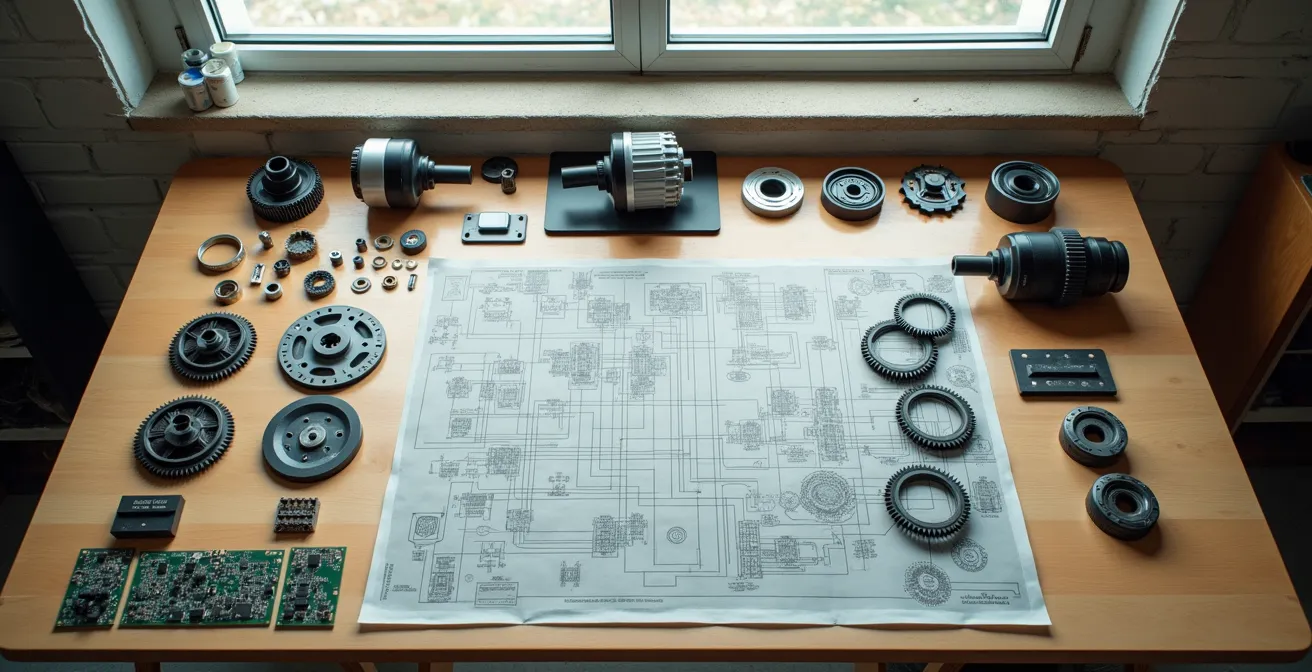

As the image shows, repairing a modern e-bike motor often means working with a collection of salvaged or third-party components. This is the tangible result of a manufacturer not providing a clear path for component-level service, turning mechanics into resourceful scavengers.

Shimano vs Bafang: Which Has Better Global Parts Availability?

The choice between a closed-ecosystem brand like Shimano and an open-source-friendly one like Bafang is a defining decision in your e-bike’s long-term repairability. It’s a classic trade-off between the perceived safety of a large, certified network and the flexibility of an open market. Neither is universally better; the right choice depends on your location, technical skills, and tolerance for risk.

Shimano operates on a closed-network model. Repairs and parts are available exclusively through their network of certified service centers. This ensures a high standard of service but limits your options. If a motor fails, the standard procedure is a full unit replacement, not an internal repair. This can be efficient but very expensive outside of warranty. Their strength lies in a predictable, high-quality global network, ideal for long-distance tourers who need reliable support in major towns.

Bafang, in contrast, represents an open-source philosophy. While they have official dealers, a massive third-party market exists for individual components—from nylon gears to controllers and speed sensors. This empowers DIY enthusiasts and independent bike shops to perform component-level repairs, drastically reducing costs. If a single gear fails in a Bafang motor, you can often buy just that gear for under $50. This approach is invaluable for riders in remote areas or those who value self-sufficiency and “parts sovereignty.”

This table from an analysis on an enthusiast forum breaks down the fundamental differences in their repair ecosystems.

| Aspect | Shimano | Bafang |

|---|---|---|

| Network Type | Closed, certified dealers only | Open-source, third-party market |

| Repair Level | System-level (full unit replacement) | Component-level (individual parts) |

| Parts Access | Through authorized centers | Direct purchase, multiple sources |

| Typical Repair Cost | €700+ for motor replacement | $20-50 for common parts |

| DIY Possibility | Very limited | Extensive with community support |

| Best For | Long-distance tourers needing certified shops | DIY enthusiasts in remote areas |

Ultimately, choosing Shimano is a bet on the longevity of the corporation and its dealer network. Choosing Bafang is a bet on the resilience of a decentralized, open market. For a buyer concerned about a company going bust, the Bafang model offers a more robust path to long-term repair, albeit one that may require more personal effort.

The Risk of DRMs Preventing Third-Party Battery Use

Digital Rights Management (DRM), a concept borrowed from the software and media industries, is one of the most significant threats to e-bike repairability. In this context, it takes the form of a proprietary “digital handshake” where the battery, motor, and display are programmed to only work with each other. If you attempt to connect a third-party or refurbished battery, the system detects a non-genuine component and refuses to function. This software lock-in is a form of engineered unavailability, designed to maintain control over the lucrative parts market.

This practice is not theoretical; it’s a major hurdle for owners and repairers. The intricate connectors and proprietary firmware are intentionally complex to thwart reverse-engineering. This forces customers back to the original manufacturer for battery replacements, often at a premium price, and renders the bike useless if the company ceases to produce that specific battery model.

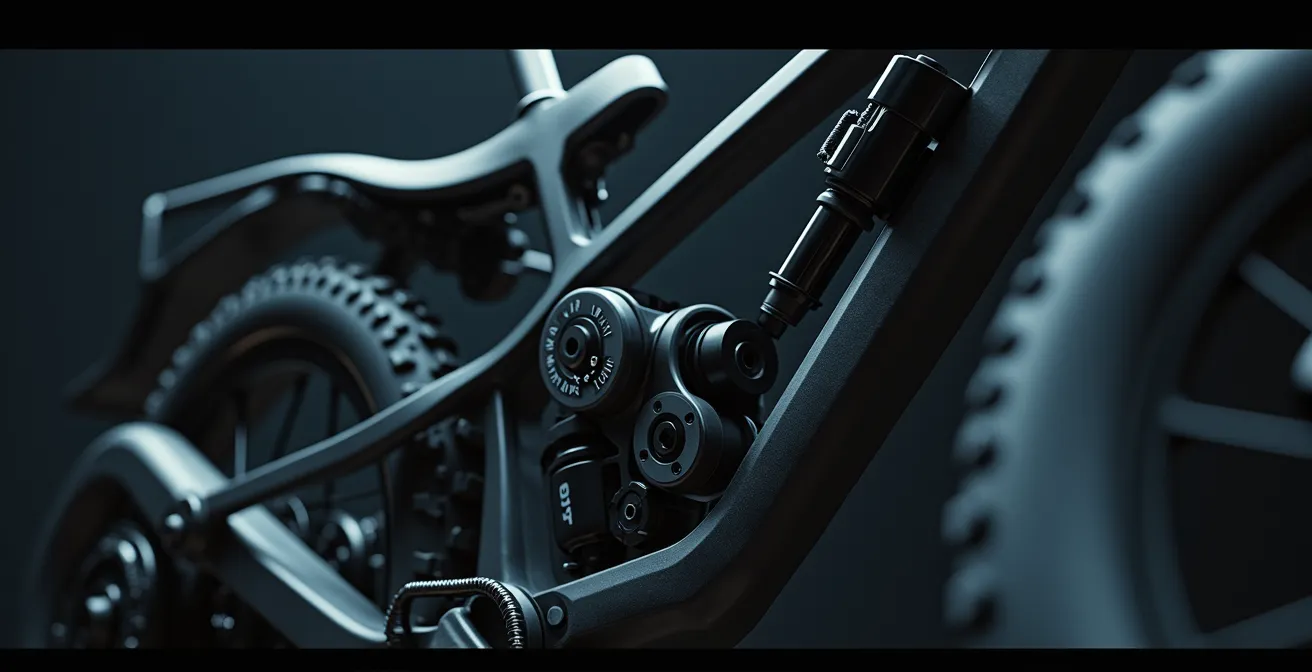

The complexity seen in this close-up of a proprietary connector is not just for performance; it’s a physical manifestation of the digital wall that prevents interoperability. Each unique pin can be part of the “digital handshake” protocol that locks out unauthorized components.

Case Study: The “Bosch Handshake” Challenge

A GitHub project dedicated to understanding the Bosch e-bike system’s “challenge-response” process reveals the scale of this problem. The project’s goal is to create compatible Battery Management System (BMS) boards. A successful outcome would “allow people to build custom batteries compatible with Bosch bikes, as well as to repair batteries with damaged BMS.” This effort by the tech community shows that the barrier to repair is not a lack of technical ability, but a deliberately imposed software lock.

The legislative landscape is also contentious. Worryingly, recent legislation developments reveal that e-bikes were removed from New York’s landmark right-to-repair law before it was signed in 2023, following intense industry lobbying. This highlights a powerful push by some manufacturers to keep their repair ecosystems closed, making it even more critical for consumers to be vigilant.

Consumables to Stock: What to Buy Before It Goes Out of Stock

While you may not be able to control the availability of a proprietary motor, you can exercise a degree of “parts sovereignty” by stocking up on system-specific consumables. These are the high-wear items that you know you will need to replace, but which may have unique specifications that make finding generic replacements difficult. Thinking ahead and purchasing these items when you buy the bike can save immense frustration later.

Beyond the obvious items like tires and tubes, focus on parts that are unique to your e-bike’s system or frame. The goal is to build a small, personal inventory that insulates you from future supply chain disruptions or a manufacturer discontinuing a specific standard. A $100 investment in small parts today could be the difference between a rideable bike and a dead one in five years.

Consider this a personal insurance policy against engineered unavailability. Here are key categories of consumables to consider stocking:

- Brake Pads: While many are standard, some high-performance e-bike brake systems (e.g., certain models from Magura or Tektro) use proprietary pad shapes. Buy at least two or three extra sets.

- Drivetrain Components: Pay close attention to the chainring. Some mid-drive motors use a unique bolt pattern (BCD) or a direct-mount interface. Having a spare chainring is wise, especially if it’s an uncommon tooth count.

- Sensors and Magnets: The small speed sensor mounted on the chainstay and its corresponding spoke magnet can be easily damaged or lost. They are often proprietary. A spare sensor is a cheap and tiny part to keep on hand.

- Display Mounts and Wires: The plastic bracket that holds your display is susceptible to breaking in a crash. These are almost always proprietary. Similarly, connector wires between components can get damaged; having a spare can be a lifesaver.

- Derailleur Hanger: This small metal piece is designed to break to protect your frame and derailleur. Every frame has a unique hanger. Buy at least two spares from the manufacturer when you purchase the bike.

By identifying and stocking these small but critical parts, you take a crucial step toward securing your bike’s long-term function, regardless of the manufacturer’s future decisions.

Why a 2-Year Local Warranty Is Worth $500 More

When evaluating the price of an e-bike, it’s a common mistake to view a longer or more comprehensive warranty as a simple “add-on.” A consumer advocate’s perspective reframes it entirely: a robust, local warranty is not a feature, it’s a pre-paid service contract and a critical financial risk-mitigation tool. Paying a $500 premium for a bike from a local shop with a two-year, all-inclusive warranty versus buying a cheaper online model with a one-year, parts-only warranty is often a wise investment.

The key distinction lies in what is covered. A “parts-only” warranty, common with direct-to-consumer brands, means that if your motor fails, they will ship you a new one. However, you are left to handle the installation. This is a complex task that most people are not equipped for, and many bike shops will refuse to work on brands they don’t sell. Even if you find a willing mechanic, a warranty comparison analysis shows that you could face $200 or more in typical labor costs for the installation, which comes directly out of your pocket.

A comprehensive warranty from a local bike shop, however, typically covers both parts and labor. If your motor fails, you simply bring the bike to the shop, and they handle the entire process—diagnosis, liaising with the manufacturer, and installation of the new unit—at no extra cost to you. This saves you not only money but also significant time and stress. This is particularly valuable during the first two years of ownership, when manufacturing defects are most likely to appear.

Furthermore, the warranty terms on replacement parts can be surprisingly limited. It’s not uncommon for a brand new replacement motor to come with only a 12-month warranty, regardless of the bike’s original warranty period. This makes having a strong relationship with a local dealer, who can advocate on your behalf, even more important. Viewing that extra upfront cost as an insurance policy against future headaches and high, unexpected bills is the savvy way to approach your purchase.

Why Chains Wear Out Faster on E-Bikes (And How to Check)

One of the most immediate and tangible differences in owning an e-bike is the accelerated wear of its drivetrain components, particularly the chain. An e-bike chain is subjected to significantly higher and more consistent forces than a chain on a non-electric bike. The combination of the rider’s pedaling force and the motor’s torque, especially when starting from a standstill or shifting under power, puts immense strain on the chain.

This increased load means that chains wear out much faster. While a chain on a regular bike might last for several thousand miles, an e-bike chain may need replacement in as little as 1,000-1,500 miles, or even sooner depending on riding style and conditions. The critical point to understand is that a worn chain (a condition known as “chain stretch”) is not just a problem in itself; it’s a catalyst for more expensive damage. As the chain elongates, it no longer fits perfectly with the teeth of the cassette and chainring, leading to premature wear and “shark-toothing” of these much more expensive components.

Because of this, the replacement threshold for e-bike chains is much tighter. According to maintenance experts, you should replace your chain at a 0.5% wear measurement on a chain checker, compared to the 0.75% standard for most non-electric bikes. Adhering to this stricter tolerance is the single most effective way to preserve the life of your entire drivetrain.

To protect your investment, a diligent maintenance protocol is not optional; it’s essential. This includes:

- Regular Checks: Use a chain wear gauge to check your chain every 200-300 miles. This simple tool is inexpensive and easy to use.

- Prompt Replacement: Replace the chain as soon as it reaches the 0.5% wear mark. Delaying this will cost you far more in the long run.

- Use E-Bike Specific Chains: Opt for chains specifically designed for e-bikes, such as Shimano’s LINKGLIDE or KMC’s “e” series. They are built with stronger pins and plates to handle the extra torque.

- Practice Smart Shifting: Avoid shifting gears while the motor is under heavy load. Briefly ease off the pedals as you shift to reduce strain.

Key Takeaways

- Your primary risk is not component failure, but a closed “repair ecosystem” that prevents you from fixing it through proprietary parts and software locks.

- Evaluate systems on a spectrum from open (like Bafang, allowing component-level DIY repair) to closed (like Shimano, requiring full unit replacement at certified centers).

- A comprehensive local warranty covering parts and labor is a critical financial tool that protects you from high, unexpected service costs.

The Hidden Value of Buying from a Certified Bosch/Shimano Service Center

In a world of proprietary parts and digital handshakes, purchasing your e-bike from a certified service center for a major system like Bosch or Shimano is arguably the single most effective risk-mitigation strategy. This decision is less about the bike itself and more about buying into a fully supported, albeit closed, repair ecosystem. The premium price often associated with these bikes is a direct payment for access, expertise, and peace of mind.

Certified centers have access to a trifecta of resources that are actively denied to independent shops and individual owners: proprietary diagnostic tools, a direct supply line for replacement parts, and the official technical documentation required to perform repairs safely and correctly. As many mechanics report, they are often forced to turn down e-bike repairs not because they lack the skill, but because the crucial information and tools are simply unavailable to them outside the authorized network.

The intent of New York’s right-to-repair law was not to give people special tools to pry open their batteries at home. The law stipulates that manufacturers must give independent shops and device owners access to the same parts, tools, and documentation they provide to their authorized repair partners.

– Cascade PBS, E-bike Right to Repair Analysis

This clarification is key. While the spirit of these laws is to open access, the reality is that major brands currently hold all the cards. By purchasing from a certified shop, you are aligning yourself with the side that has guaranteed access. When a complex electronic issue arises, the certified mechanic can plug your bike into a diagnostic computer, read the error codes, and order the exact part needed—a process that is simply impossible for an unequipped third party.

This doesn’t invalidate the open-source path, but it frames the choice clearly. Buying from a certified center is an acceptance of the closed-system model in exchange for a guarantee of service. For the buyer whose primary fear is being left with an unsupportable “brick,” this is often the most logical and reassuring path to long-term ownership.

Ultimately, the power lies in your pre-purchase diligence. By asking these tough questions and prioritizing long-term serviceability over short-term features, you transform yourself from a passive consumer into an empowered owner. The next logical step is to use this knowledge to assess potential bikes not just on their spec sheet, but on the strength and openness of their repair ecosystem.