Relying on your smartphone for serious bike touring is a gamble against predictable failure points that a dedicated GPS is built to withstand.

- Constant handlebar vibration can permanently destroy your phone’s advanced camera systems (OIS), a costly and often overlooked risk.

- Phone screens (OLED) are designed for indoor viewing and become nearly unreadable in direct sunlight, while dedicated GPS units use transflective screens that become clearer in bright light.

- “Offline maps” on phones often lack true offline re-routing capabilities, leaving you stranded in no-service zones where a dedicated unit would thrive.

Recommendation: For rides over 50 miles or any remote touring, invest in a dedicated GPS unit for reliability and safety. Use your phone as a backup and for off-bike tasks.

You’re kitted out, the route is planned, and the open road calls. The final piece of the puzzle is navigation. The debate rages in every cycling forum: is the powerful smartphone in your pocket sufficient, or is a dedicated GPS unit from Garmin or Wahoo a non-negotiable piece of gear? Many cyclists assume their phone, with its slick interface and countless apps, is a perfectly capable co-pilot. They download an app, buy a cheap mount, and hit the road, thinking they’ve saved a few hundred dollars.

This approach often focuses on surface-level arguments like battery life and cost. However, for any ride that pushes beyond the city limits, this thinking overlooks the critical, hidden failure points that can turn a dream tour into a frustrating or even dangerous ordeal. The real difference isn’t about convenience; it’s a fundamental question of system integrity and risk management when you’re miles from home.

But what if the most significant risks aren’t the obvious ones? What if the very vibrations from the road are silently destroying your phone’s most expensive component? Or if your “offline” map is a useless image the moment you miss a turn in a dead zone?

This guide moves beyond the simple pros and cons. We will dissect the technical vulnerabilities that separate these two device categories. We’ll explore why phone screens fail in the sun, how handlebar mounts can lead to expensive repairs, and what “true offline capability” really means for a touring cyclist. By understanding these failure points, you can make an informed decision based on safety and reliability, not just features.

To help you navigate this technical landscape, we’ve broken down the core issues into distinct sections. This structure will guide you from understanding the fundamental risks to choosing the right software for your adventures.

Summary: Smartphone vs. GPS: A Cyclist’s Technical Deep Dive

- Why Using Your Phone for GPS Can Leave You Stranded

- How to Download Maps for Remote Areas Without Data Coverage

- OLED vs Transflective Screens: Which Is Readable in Direct Sunlight?

- The Risk of Destroying Your Phone Camera on Handlebar Mounts

- Updating Maps: The Routine Check Before Every Long Weekend

- The Danger of Cloud-Based Planning in No-Service Zones

- Deciphering Common Bosch/Shimano Error Codes at Home

- Komoot vs Strava: Which Planner Is Best for E-Bike Touring?

Why Using Your Phone for GPS Can Leave You Stranded

The most romanticized image of bike touring is one of self-sufficiency and freedom. The single greatest threat to this is an equipment failure that leaves you lost, and your smartphone is a device with multiple, compounding points of failure. While a dead battery is the most cited concern, it’s only the beginning of the story. The real problem is system instability under conditions that a dedicated GPS unit is specifically engineered to handle.

First, consider thermal management. On a hot, sunny day, a phone mounted to your handlebars is exposed to direct sunlight and high ambient temperatures. Running GPS, a bright screen, and processing data generates significant internal heat. Unlike a dedicated unit, a phone isn’t designed for this. It will automatically dim its screen to an unreadable level or shut down completely to protect its internal components, leaving you without a map at a critical moment. This isn’t a bug; it’s a self-preservation feature that is fundamentally at odds with the needs of a touring cyclist.

Second, software reliability is a major vulnerability. Your phone is a complex ecosystem running dozens of background processes, from social media notifications to email syncs. Any one of these can cause the operating system or your navigation app to crash. A sudden software freeze or an unexpected “low memory” error can force a restart, which is a major hassle when you’re trying to navigate a complex junction and a massive problem if it happens in an area with no cell service to reload the map.

Finally, the battery issue is more nuanced than just capacity. A phone’s battery is designed for intermittent, varied use. Constant GPS tracking with the screen on creates a high, sustained power drain that degrades battery health over time. A dedicated GPS unit, by contrast, uses a low-power chipset and a power-efficient screen, allowing it to run for 15, 20, or even 40 hours on a single charge. It does one job, and it does it with extreme efficiency, ensuring it’s still running when you need it most.

How to Download Maps for Remote Areas Without Data Coverage

One of the most common rebuttals from phone advocates is, “I just download maps for offline use.” While true, this statement dangerously oversimplifies the reality of what “offline” means. There is a vast technical difference between downloading a static map image and having a true offline routing engine. This distinction is arguably the most critical factor for any cyclist venturing into areas with intermittent or non-existent data coverage.

Most basic navigation apps simply cache map tiles—essentially pictures of the map. If you stay on your pre-planned route, this works fine. The moment you take a wrong turn, miss an exit, or encounter an unexpected road closure, the app is useless. It cannot calculate a new route without a data connection because the routing logic resides on a server. You are left with a pretty picture of where you are, with no intelligence to guide you back.

True offline navigation, as offered by apps like Komoot and premium versions of others, downloads not just the map tiles but the entire vector dataset and the routing algorithm itself. This means the app can perform dynamic on-device re-routing without any internet connection. If you need to detour, it can create a brand new turn-by-turn route to get you back on track, just as it would with a full data signal. This is the standard functionality of any dedicated GPS computer.

As the table below illustrates, the way different platforms handle offline data can have a major impact on your trip’s safety and flexibility. Choosing a service with robust offline capabilities is essential for peace of mind in remote regions.

| Feature | Komoot | RideWithGPS |

|---|---|---|

| One-time World Access | $29.99 lifetime | Not available |

| Offline Navigation | Voice navigation included | Premium only ($9.99/mo) |

| Map Type | Vector maps | Mixed raster/vector |

| Route Modification Offline | Yes | Limited |

| Storage Requirement | ~100MB per region | ~200MB per region |

OLED vs Transflective Screens: Which Is Readable in Direct Sunlight?

You’re riding under a brilliant summer sky, but you can’t see your map. You squint, shield the screen with your hand, and crank the brightness to 100%, draining your battery, yet the route remains a faint, reflective ghost. This experience is a universal frustration for cyclists using a smartphone for navigation. The problem isn’t a lack of brightness; it’s the fundamental technology of your phone’s screen.

Modern smartphones almost exclusively use emissive screens like OLED or LCD. These screens work by generating their own light, projecting it from behind the pixels towards your eyes. In a dark room, they look vibrant and beautiful. However, in direct sunlight, they are fighting a losing battle against the most powerful light source in our solar system. The sun’s ambient light washes out the screen’s projected light, causing massive glare and making it nearly impossible to read. Pushing the brightness higher only provides a marginal improvement while rapidly depleting the battery.

Dedicated GPS units use a completely different, and arguably superior, technology for this specific use case: the transflective screen. A transflective screen has two modes. In low light, it uses a backlight to illuminate the display, just like a phone. But in bright sunlight, it does something clever: the backlight turns off, and a reflective layer *behind* the pixels uses the sun’s own light to illuminate the screen. The brighter the sun, the more light there is to reflect, and the clearer and more contrasted the screen becomes. It works *with* the sun, not against it.

This is why a Garmin or Wahoo screen, which can look dull and washed out indoors, is perfectly crisp and readable on the sunniest of days, all while using a fraction of the power. Furthermore, this difference in hardware impacts accuracy; independent testing reveals that dedicated units maintain better signal and tracking precision compared to the power-hungry, multi-tasking chipsets in phones.

The Risk of Destroying Your Phone Camera on Handlebar Mounts

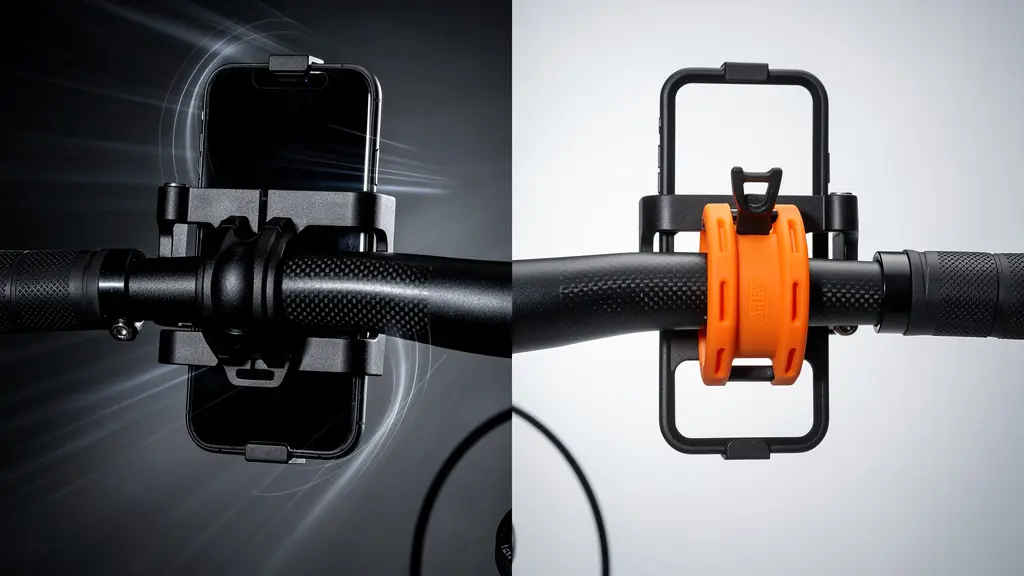

Perhaps the most insidious and least-understood risk of using a smartphone on a handlebar mount is the potential for permanent, expensive damage to its camera system. Modern flagship phones from Apple, Google, and Samsung feature sophisticated Optical Image Stabilization (OIS). This technology uses tiny, free-floating lens elements controlled by electromagnets to counteract the shake from your hands, producing sharp photos and smooth videos. It’s a marvel of micro-engineering, but it has a critical vulnerability: high-frequency vibrations.

A bicycle, even on a smooth road, transmits a constant stream of high-frequency vibrations up through the frame and into the handlebars. A rigid mount transfers this energy directly into your phone. Over time, these vibrations can overwhelm the delicate OIS mechanism, causing the electromagnets to fail or the lens elements to become misaligned. The result is a camera that can no longer focus, produces a constant jitter or “buzzing” sound, and is effectively destroyed. This is not a theoretical risk; it’s a well-documented problem.

Case Study: The Vibrating iPhone XS

In a report highlighted by iFixit, journalist Brian X. Chen found his iPhone XS camera’s OIS system was permanently damaged after mounting it on his motorcycle for navigation. Even though the motorcycle was a lightweight model with moderate vibrations, the constant exposure was enough to require a complete camera module replacement, a problem that cost hundreds of dollars to fix.

Apple itself explicitly warns against this. In an official support document, the company states:

It is not recommended to attach your iPhone to motorcycles with high-power or high-volume engines due to the amplitude of the vibration in certain frequency ranges that they generate.

– Apple Support, Apple Official Support Document

While this warning specifies motorcycles, the principle applies directly to the constant, high-frequency “road buzz” of cycling. The only way to mitigate this risk is to use a specialized mount with a vibration-dampening module, which adds significant cost and complexity, bringing the total price closer to that of an entry-level dedicated GPS unit that is, by design, immune to this problem.

Action Plan: Protecting Your Phone’s Camera

- Identify Your Risk: Check if your phone model has OIS. Most flagships since the iPhone 6 Plus and equivalent premium Android devices do.

- Invest in Dampening: If you must mount your phone, use a high-quality system with a dedicated vibration dampener module, like those offered by Quad Lock or Peak Design.

- Limit Exposure: Even with a dampener, minimize the time your phone spends on the mount. Use it for complex navigation sections and store it for long, straight stretches.

- Consider a “Burner” Phone: Use an older, cheaper phone without OIS as your dedicated cycling computer. Its camera is not at risk.

- Perform Regular Checks: After each long ride, open your camera app and test its focus at various distances to catch any early signs of jitter or damage.

Updating Maps: The Routine Check Before Every Long Weekend

Whether you choose a dedicated GPS or a smartphone, your navigation is only as good as its data. Roads change, trails are rerouted, and points of interest open and close. Heading out for a multi-day tour with outdated maps is a recipe for frustration. Establishing a pre-ride digital checklist is just as important as checking your tire pressure or lubing your chain. This routine ensures your technology is ready for the journey ahead.

The first step, often overlooked, is to update the device’s firmware or the navigation app itself. Developers frequently release updates that improve map rendering speed, fix battery consumption bugs, or enhance routing algorithms. Running the latest version of the software is crucial for optimal performance. This should be done at home on a stable Wi-Fi connection, ideally a few days before you depart to ensure there are no new bugs.

Next comes the map data itself. For dedicated GPS units, this means connecting to a computer and using the manufacturer’s software (like Garmin Express) to download the latest map versions. For phone apps, it means going into the app’s settings and triggering an update for your base maps and any specific regions you’ve downloaded for offline use. Do not assume this happens automatically.

The final, and most critical, part of this routine is the “Airplane Mode Test.” After all updates are complete, put your device into airplane mode. Now, try to load the route for your trip. Zoom in and out on various sections. Try to plan a new, short route from your current location to a point within the offline map area. If the map loads instantly and all functions work, your device is ready. If it lags, shows blank spots, or fails to route, you have a problem that is far easier to solve on your home Wi-Fi than on the side of a remote mountain road.

The Danger of Cloud-Based Planning in No-Service Zones

The convenience of planning a route on your desktop and having it magically appear on your device is a modern marvel. However, this convenience often hides a dependency on the cloud that can become a significant liability. The danger lies in how your chosen app or device handles your routes when it can’t “phone home” to its server. A system that is heavily cloud-dependent can fail you completely when you need it most.

Many popular platforms, especially those with a strong social component like Strava, are designed around a constant connection. Your routes, segment data, and even some map layers are streamed from the cloud. While they may offer a basic “offline route” feature, it often just saves the GPX track as a line on a blank background. There’s no underlying map data and certainly no ability to re-route if you go off course. This is a fragile system for remote touring.

A truly robust planning ecosystem prioritizes local data storage and processing. When you plan a route in an app like Komoot, sending it to your device for offline use downloads all the necessary Turn-by-Turn navigation cues, points of interest, and underlying vector map data. The device becomes a self-contained navigation unit. This is critical because it means you can not only follow the route but also modify it, re-route around an obstacle, or find your way back to it after an unplanned stop, all without a single bar of cell service.

The following table breaks down the cloud dependency of major navigation apps, highlighting which are suitable for emergency use in no-service zones. This is a crucial consideration for anyone planning to ride outside of reliable network coverage.

| App | Offline Re-routing | Cloud Dependency | Emergency Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Komoot | Yes – full turn-by-turn | Low | Excellent |

| RideWithGPS | Premium only | Medium | Good |

| Strava | No | High | Poor |

| AllTrails | Limited | High | Fair |

Deciphering Common Bosch/Shimano Error Codes at Home

For the growing number of cyclists embracing e-bike touring, a new layer of technical complexity arises: the drive system. An unexpected error code flashing on your display can be a source of major anxiety. While some issues require a certified mechanic, many are simple sensor or connection problems that you can resolve yourself on the road. Knowing how to decipher the most common error codes from major systems like Bosch and Shimano STEPS can be the difference between a ride-ending failure and a minor five-minute fix.

These error codes are not arbitrary; they are diagnostic tools. They are categorized by severity, from simple warnings that don’t affect performance to critical faults that will shut down assistance. The first step is not to panic, but to identify the code and understand its meaning. For example, a common Bosch `E010` or Shimano `W011` code is often just a warning about temperature or a temporarily misaligned speed sensor magnet.

The most common user-fixable issues relate to three areas: the speed sensor, battery connections, and power cycling. The speed sensor, usually a small magnet on a wheel spoke and a sensor on the chainstay, can get knocked out of alignment or covered in mud, leading to an error. Simply cleaning it and ensuring it’s properly aligned (usually 2-5mm gap) can resolve many issues. Similarly, a Bosch `504` error often indicates a poor battery connection; removing and firmly re-seating the battery can often clear the fault.

Finally, the classic “turn it off and on again” is a valid troubleshooting step. A power cycle can reset the system’s controller and clear temporary glitches, such as a Shimano `E503` error. The table below serves as a quick field guide to some of the most common codes you might encounter.

| Error Code | System | Severity | Field Fix |

|---|---|---|---|

| E010 | Bosch | Continue Riding | Check speed sensor magnet alignment |

| E503 | Shimano | Limp Mode | Power cycle system, check connections |

| 504 | Bosch | Ride-Ending | Battery connection issue – reseat battery |

| W011 | Shimano | Warning Only | Temperature warning – let motor cool |

Key takeaways

- The choice is a risk assessment: a phone’s vulnerabilities (camera damage, overheating, poor screen visibility) are liabilities on long tours.

- “Offline maps” are not created equal. True offline capability includes on-device re-routing, a feature standard on GPS units but rare on free phone apps.

- Dedicated GPS units are purpose-built tools that excel in the exact conditions where smartphones fail, making them a wise investment for serious cyclists.

Komoot vs Strava: Which Planner Is Best for E-Bike Touring?

Once you’ve chosen your hardware, the software—your route planning tool—becomes the brain of your operation. For many, the choice comes down to two giants: Strava and Komoot. While Strava is the undisputed king of social tracking and competitive segments, its utility as a serious touring planner, especially for e-bikes, is limited. Komoot, on the other hand, is built from the ground up for exploration and adventure, with features that are particularly beneficial for e-bike tourers.

Strava’s primary function is performance analysis. Its route planner is a secondary feature, and it lacks the granularity needed for multi-day touring. It treats all roads similarly and offers minimal information about surface type or terrain challenges. For an e-bike rider, this is a critical flaw. You need to know if a route includes long stretches of soft gravel or a series of steep, technical climbs that will drain your battery much faster than anticipated.

This is where Komoot excels. Its planner is a powerful tool for discovery. A detailed analysis shows that Komoot’s e-bike specific routing considers factors like surface type (paved, gravel, singletrack) and elevation profiles to provide more realistic time and difficulty estimates. It will actively warn you if a path is unsuitable for a touring bike, a feature Strava lacks. Furthermore, Komoot’s “Highlights” feature, which crowdsources points of interest from other users, is invaluable for discovering scenic viewpoints, cafes, or bike shops along your route.

Moreover, Komoot’s business model is better aligned with the needs of a tourer. While Strava locks its best features behind a recurring subscription, Komoot offers a compelling one-time purchase option. A recent comparison reveals that a single £29.99 fee can unlock worldwide offline maps forever, making it a cost-effective and powerful investment for any serious cyclist. This combination of detailed planning, e-bike awareness, and robust offline functionality makes it the superior choice for planning your next adventure.

Ultimately, the decision comes down to a clear-eyed assessment of your needs. For casual urban rides or short, well-supported day trips, your smartphone is a capable tool. But for the aspiring tourer, the bikepacker, or anyone whose rides take them beyond the reach of cell towers and easy help, the dedicated GPS unit is not a luxury; it is a fundamental piece of safety equipment. It is an investment in reliability, durability, and peace of mind.